To LJF,

To LJF,

My dad is dead. The finality of the prose beats like a hammer on a nail. My dad. Is dead. This is the day that I dreaded for my entire life.

There is a howling, gaping chasm in the world today. The deflated clothes hanging in the laundry room where I dressed this morning. The advice on the new car that he won’t be there to give. The pictures that I will take for him at Normandy next month before I realize that he won’t be here to see them. That hammer blow will strike again and again.

Let it come. Let this hurricane roar, let it tear me to shreds. Let its size match his. This searing force testifies to his greatness, his goodness, his bigness. This pain honors him.

Because he was a big man. Physically large in ways that made us terrified, even angry, that this day would come sooner than it has. Yet, from haggis to boudin, he just couldn’t say “no” to a juicy sausage. Even now, in the refrigerator, a smoked jalapeno link awaits his fork. And his appetite for pasta and garlic made his own mother question his ethnicity, sure that the hospital had switched him with the Italian baby born the same night. He liked his food. But physical size, that’s just a metaphor. His bigness came in all forms. He had presence. He will be an absence.

And, god, that presence was funny. No one here should be surprised that his humor came in various shades of blue. He enjoyed fart jokes so much that I cannot judge them on their own merits. His laughter at the campfire scene in Blazing Saddles entered ranges heard only by dogs; and the Symphony Moose I’m sure haunts the Miller Outdoor Theater to this day, fumigating the station wagons of unsuspecting families. Yet, he had a touch of sophistication and wit. What other father would introduce his eleven-year old daughter to Chaucer via the extended Middle English fart joke, “The Miller’s Tale”?

Still, with all the bawdy shenanigans, you could watch the emotion roll through him as he listened to Elgar’s “Nimrod.” “Amazing Grace” played by the Black Watch reduced him to tears, and he wept at the mere description of hearing Vivaldi’s “Four Season” played live in San Vidal Cathedral in Venice. When Karl and I were small children — in the time before Keith — we curled up on the sofa with him, eating applesauce straight out of the jar and listening to Bedrich Smentana’s “Die Moldau” as he described the song’s fairy tales scenes along a river in central Europe.` My earliest memories of music came wafting down the hall with the strains of Beethoven that he played on Sunday mornings. I can see him sitting in his garage shop as I drive up, surrounded by cases, tools at arms’ length, testing the horn on his lap. Beauty came to him through sound.

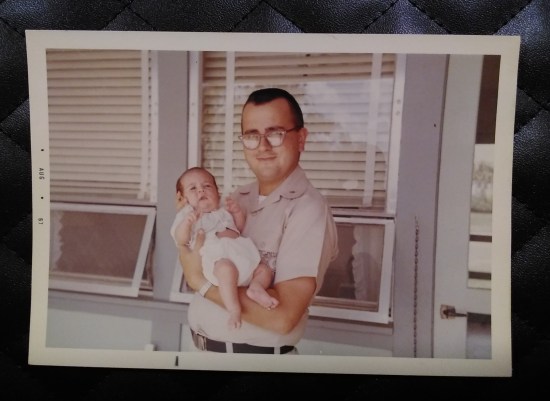

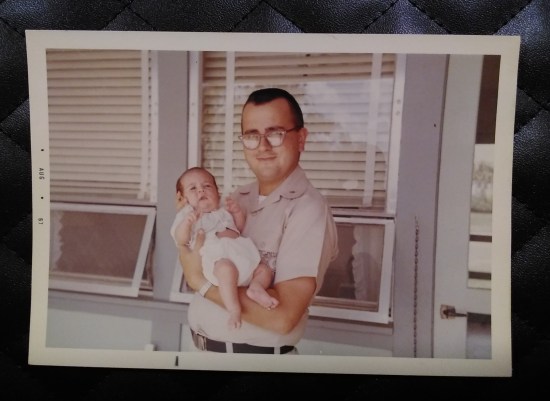

And not since the nineteenth century has anyone elevated sentimentality to such a virtue. That pure, sweet smile he had for dogs, babies, weddings. Was there not a time in his life when a hound sat on his lap? There was the holy trinity and a half of dachshunds, Rascal, Gretl, Fritz, and Frida the chiweenie, with the bassets Klyde and Sousa in between. And babies! He had no shame, waving and making faces at them in restaurants, stores, museums. We went on a tour of the Seward House up where I live, and he made a bee-line for a lady with an infant on the tour. He fawned and cooed until that little pudge giggled at the funny white haired man with walrus mustache. How poetic that his own first baby was me and his last was Claire, the daughter of his youngest son: two girly-girls with foul mouths and a penchant for pink, bookending four very boyish boys — Karl, Keith, Jake, and Bradley. Then, the gratitude that we three — Karl, Keith, and I — found our partners, our person, who would enlarge the love he felt. Dad grew up a little prince in an extended family, wrapped in the certainty and safety of love. This he wanted for us, for all of us here. Extending his love.

For he was a man of great empathy and emotion, more than was encouraged in men of his generation — of men in most generations. He alone could find the strength to sympathize Velma Kemp, that principal-of-the-world mother-in-law. He saw beyond her thick, bitter crust to the frail, lonely old woman who had alienated everyone by her final years. And he could sit with anyone, any type of person no matter how different they were from him, and interview them about their lives out of pure curiosity and without judgement. At my doctoral graduation, he looked over to see him asking my radical lesbian Persian friend about fleeing the Iranian Revolution as a child. Yet, the sight was not at all incongruous, but warm, in keeping with him, and the curiosity about individuals that broke down prejudices about groups.

So, really, his biggest presence — and now his biggest absence — will be on the other side of a conversation. We pondered great spiritual matters conducting a seance with my Ouija board when I was twelve, and worked through big ideas of life, the universe, war, history as we built my dollhouse, or he tooled around the garage, or while he worked on Big Bird my yellow Buick Skylark. He loved that car — my car — so much because it was one of the last cars he could really work on using old school mechanics skills. Whatever we talked about when he helped move me from Indianapolis to Boston, I really do not remember. Riding across country together, sharing a joke about being followed by a green Mazda the whole way – my car in tow behind the moving van — filled me with warmth and an aching sense of the fragility of those days.

Most of all, he tried to hear what you meant below the words you were saying. Because he listened, because he genuinely sympathized with you, and took whatever blow you offered to discover the source of conflict. He was someone who, no matter how angry you became with him or he with you, would always forgive. You could depend on him. His love was stalwart.

He told me a story of putting together a bookshelf with his grandson. As a father, he said, he would have become frustrated at how long the process took because his focus would have been on the task of construction. Now, as a grandfather, he had realized that the point was not the bookshelves but the time with this charming, impish little boy. By that measure, putting together a bookshelf with his grandson should take hours, days, weeks. He wished he had figured that out earlier. He was glad that Karl and Keith did.

I have finally begun to hear him through all of my own noise, to finally realize what he had been trying to tell me even as he himself figured it out. Time doesn’t just pass quickly. It accelerates. And love demands epic courage. Anger, resentment, guilt, fear, disappointment, dread — work those out quickly or don’t waste your time on them. You receive this gift of another life in yours and you will never, ever have enough time with them. Losing them will always feel unbearable. Dad, I understand now. I wish I had the strength to hear you all along.

Only the most gifted of poets have the skills and the fortitude to transform agony into beauty. So, I turn to a poem by W.H. Auden. The words have returned to me every day of this last wretched week:

Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone.

the dog from barking with a juicy bone,

Silence the pianos and with muffled drum

Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come.

Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead

Scribbling in the sky the message He is Dead,

Put crepe bows round the white necks of the public doves,

Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves.

He was my North, my South, my East and West,

My working week and my Sunday rest

My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song;

I thought that love would last forever, I was wrong.

The stars are not wanted now; put out every one,

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun.

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good.

I’m sorry for all of the bad times, Daddy, and the times I was ungrateful. Thank you for my life. Thank you for yours. I loved you so much. I always will.

A new feeling begins in preparations for Normandy, a trip that coalesced ages ago. For practical purposes you can say the planning began when you accepted the invitation to speak about Frederick Douglass in Paris. Arrangements continued when your husband’s daughter’s wedding date, bounced around the calendar by the British Army for which her fiancé works, finally settled on a date two weekends before the conference. Why return to the U.S. to teach a single class before taking off for Europe again? Why not just stay? You feel exceedingly extravagant, not a tiny bit guilty, and very much relieved.

A new feeling begins in preparations for Normandy, a trip that coalesced ages ago. For practical purposes you can say the planning began when you accepted the invitation to speak about Frederick Douglass in Paris. Arrangements continued when your husband’s daughter’s wedding date, bounced around the calendar by the British Army for which her fiancé works, finally settled on a date two weekends before the conference. Why return to the U.S. to teach a single class before taking off for Europe again? Why not just stay? You feel exceedingly extravagant, not a tiny bit guilty, and very much relieved. You wake up surprised. You don’t remember going to sleep. You don’t really remember sleep. Your mind already writes the eulogy. The same words going over and over, hammering in your head have broken through to more words that can describe this moment.

You wake up surprised. You don’t remember going to sleep. You don’t really remember sleep. Your mind already writes the eulogy. The same words going over and over, hammering in your head have broken through to more words that can describe this moment. You wonder into which stage of grief Kubler-Ross would classify “Don’t Give a Fuck.” A friend suggests anger or depression.

You wonder into which stage of grief Kubler-Ross would classify “Don’t Give a Fuck.” A friend suggests anger or depression. This is not the same numbness of the ICU days, of knowing potentialities and holding them all at bay.

This is not the same numbness of the ICU days, of knowing potentialities and holding them all at bay. At one point in the day, you begin to wonder if they believe you are Jewish and are accommodating your sitting shiva, this is how long and how often you must wait.

At one point in the day, you begin to wonder if they believe you are Jewish and are accommodating your sitting shiva, this is how long and how often you must wait. To LJF,

To LJF, The words can hardly form in her mouth for the grief. You know. You see his white hair, the pink of his scalp. An emptiness begins opening. You don’t feel it at first, but you see it widening as time stretches, suspending you in this moment between unreality and the inevitable real of the fact.

The words can hardly form in her mouth for the grief. You know. You see his white hair, the pink of his scalp. An emptiness begins opening. You don’t feel it at first, but you see it widening as time stretches, suspending you in this moment between unreality and the inevitable real of the fact.