Six weeks since his death.

Six weeks since his death.

You are becoming an alcoholic. This develops not from a desire to drown your sorrows but from an inability to address them. There is this party. Another this Saturday. Another the next Saturday. Halloween festivities, plays to attend, deadlines that had extensions that required more extensions, papers to grade, classes to prepare. Your book is a finalist for another prize. Your book lives its best life. Yours proves a bit more complicated.

Everyone around you celebrates. You must not become the spectre at the feast. Everyone around you stresses. You just returned from three weeks Europe for a wedding and a conference. Who are you to wear black, now? To complain? The funeral is over. Time, distance, good news.

People ask how you are, “are you ok?” You feel as if they want reassurance that everything is back to normal, that the wound is healing. You try to be honest, you try not to worry them. You lie. You hate the armored shell that grows around you each time you do because it feels like a betrayal of him. It feels like it puts that same armor between you and your grief for him.

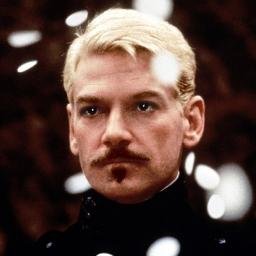

You feel like Hamlet at the beginning of the play: “I am too much in the sun.” (Hamlet is, at its core, simply a story about grief.)

Every morning you wake as if opening your eyes at the bottom of a lake. Watery anger and resentment envelope you, rise above you, compress and fill you. You drown in them.

This anger and resentment has its place along side the sadness. You welcome all of them. You would like to have a feast with these spectres. The purity of sadness rips open a chasm, dark and empty, but in it you connect to him, feel him close, concentrate your memory to gather moments and save them from this sieve that has become your mind. You must sit quietly, alone, to do this. Instead, festivities, plays, deadlines, papers, classes, your book’s best life, too much in the sun. The interference feeds the anger.

Some of the anger has its own place; but, like the sadness, the anger cannot play itself out because of the aggravation of daily life. Worse yet, the anger drains you with the effort to contain it, to keep it from letting you do something self-destructive, to keep it from spilling on to other people, to keep from blaming other people, to keep from lashing out at people who only offer compassion and advice, or who simply cross your path at the wrong moment.

You want to shout to anyone in earshot to just stay out of your way, to just let you be angry, to not become road bumps in this thing you are enduring. Let you endure it. Let you wallow in it. Let you turn it into something else, something beautiful or terrible or useful or anything that does not fester or rot or dry up in a box in the back of your mind. Let you indulge yourself to find the creative rituals that will honor this pain that honors his life.

Instead, you must control yourself. You must control the anger. You must control the sadness. You must attend the festivities, the plays, the deadlines, the grading, the classes. You care less and less about these things. You care less and less about anything and everything that is not about grief. Instead of sad, you become numb. Becoming numb makes you sad, which then makes you angry, and then you must control your anger. Your anger grows, wraps itself into depression, frustration, exhaustion, borderline alcoholism. The alcohol, at least, wipes away the controls, the numbness, the frustration, and takes you down to the pure pain of loss. Only that purity can produce anything worthwhile.