You wake up surprised. You don’t remember going to sleep. You don’t really remember sleep. Your mind already writes the eulogy. The same words going over and over, hammering in your head have broken through to more words that can describe this moment.

You wake up surprised. You don’t remember going to sleep. You don’t really remember sleep. Your mind already writes the eulogy. The same words going over and over, hammering in your head have broken through to more words that can describe this moment.

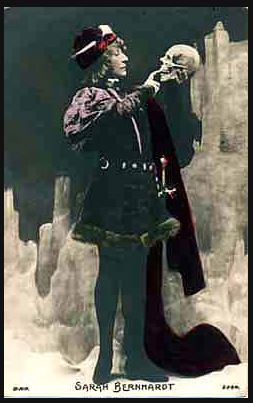

All of the metaphors and images come from films, songs, books, poems. The opening scenes from The Big Chill. “A Hole in the World.” Marley dead as a coffin nail. “Words, words, words.” “It must be the coldest day of the year” (metaphorically speaking because this is Houston). “Stop all the clocks…for nothing now can ever come to any good.” You create a patchwork quilt of pop cultural scraps. You want this to be original, although you do know that you will follow the model of Four Weddings and a Funeral, that you will use Auden’s “Funeral Blues.” The rest must be original. The rest will be the last word, the public word, perhaps the only word that a room full of people will hear you say to him. The rest must be honest.

You write. You write. You write. The light grows. People awake. The eulogy has exhausted you and the deadline looms for the obituary. Two obituaries, one long, one short. The short obituary must act as advertisement for the long. The short must be done by noon. The short must not be expensive. All the short says is that he worked at these places, belonged to these organizations, that the funeral will be at this place and at this time, donations in lieu of flowers.

The long you see as a the Authorized Biography. This will be the last, most complete, public record of his life. So, you pepper your aunt and your mother with questions. “What years did he go to Catholic High?” “When did he start playing the trumpet?” “When did he start flying lessons?” “Were you all stationed anywhere else but Texas?” “What did he major in?” “When did you meet?” “How did you meet?” You begin to realize how very little you knew of your father. You know more details about the life of a long dead man than you do about the one who raised and loved you.

The last time that you visited, you had also gone to Dallas and seen, after a lifetime of living in Texas, Dealey Plaza. You had asked your parents about learning of JFK’s assassination. You now think of that story, that gem. You think of the number of gems like that, the stories that he told about life in a receding past, or about people who had only just died of the generation before and theirs of the generation before them. Where are those stories? On what part of your hard drive have you stored them? How can you get them back? Download them, print them out, play them back? How many more did he have? Him telling those stories, kicked back in his recliner, a dog on his lap. He was the Source.

You must distill this to his essence, to the things that he loved and the things that gave his live meaning to him. His parents’ meeting through music, their World War II experience, his formation in a large, extended family, his love of music and flight, his sense of responsibility and service.

You must get this down because, even now as you write this sentence here, you feel it all gliding off of the tips of your fingers and evaporating. You want to write his stories down with blades on your skin so that you will not forget. So that you will remember that you did forget. So you will remember that you did not even gather them in the first place.

The minister and his wife arrive in the afternoon. Your parents, while secularly Christian and essentially believers in a Higher Power, weren’t particularly religious in your life. “We grew up in the Church of Don’t Get Up Early on Sunday Mornings — or Saturday Mornings,” you always joke. The minister, however, had been an old friend of your dad’s since the 1980s, and the two had talked over much spiritual business. He’s an intellectual about these matters and your dad appreciated that, you see. They could discuss and explore ideas. He’s funny, too. You see how he and your dad were such good friends. You feel connection to your dad with him next to you on the sofa discussing this thing that must be done.

You plan the service. Sort through the songs, the verses, the readings. The religious element makes you uncomfortable, but then, your dad wanted that. Your mom later tells you that all of their friends and dad’s family will expect it and want it as part of the ritual. After the planning, while everyone chats, the minister tells stories about the early days of his friendship with your dad. Suddenly, you have a visceral realization that this is his loss, too. He needs the religious element. He will be offering a funeral service for a friend of nearly thirty years, and he probably knew your dad better than you did. You no longer feel him as just a friend of your dad’s but as a compatriot in this thing you must go through.

The minister and his wife depart. You, your mother, and your aunt eat on the ten cold pizzas that your cousin brought over the day before, a stand-in for the ubiquitous Southern casseroles. Your brother wants tacos. He goes for tacos. You, on the other hand, might puke up the pizza. Alcohol quietly flows. The eulogy has a beginning and an end, but the middle does not quite gel. You finish the long obituary.

“Do you want to hear?” you ask your mom, your aunt, and your brother. They glance at each other. Looking back now, you realize that they probably did not and were being polite. You begin, “At the beginning of his story….”